Read This: A Natural History of Empty Lots

As a child growing up in small-town South Carolina, in an era before smartphones or computers, I spent long summer days and weekends exploring outdoors. My parents had bought a modest house in a new neighborhood still under construction — a wonderland for children free to occupy themselves however they saw fit until dinnertime. Around our house were wooded lots where my sister and I and neighborhood friends constructed forts out of branches; muddy ditches stubbled with crawdad mounds; shallow creeks that could be crossed on fallen tree trunks, where minnows could be caught in glass jars; and forested belts of sweet gum, shortleaf pine, and white oak, where we rolled abandoned tires and wooden cable spools and made BMX-worthy bike trails we dubbed Dead Man’s Hill and the like. We didn’t worry about trespassing and got yelled at a few times for it, but it was largely a world without fences or other barriers. I climbed trees, scrambled into gullies, poked around in framed-out shells of houses, watched out for spiders and snakes, and brought home the occasional toad, salamander, and bunny.

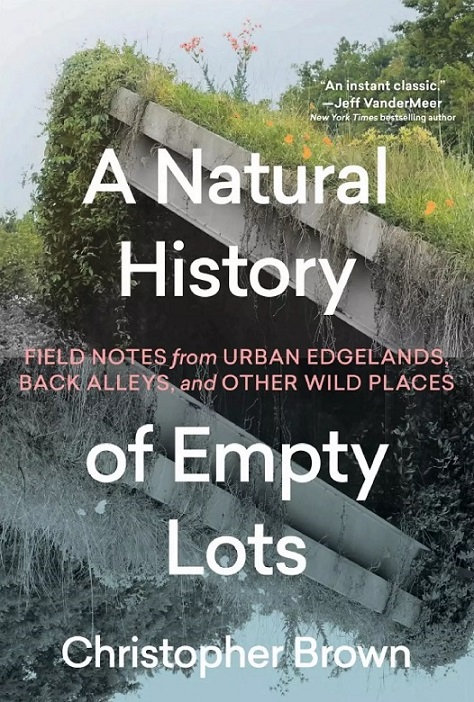

Eventually we moved to an older, more established neighborhood, and I grew into a teenager more interested in looking for boys at the mall, and I stopped seeking out semi-wild edgelands to explore. But a new book by Austin author Christopher Brown has sparked memories of those feral childhood adventures. A Natural History of Empty Lots: Field Notes from Urban Edgelands, Back Alleys, and Other Wild Places (2024) is equal parts nature writing, memoir, and eco-criticism. It’s an Anthropocene love letter to nature — the pockets of it that hang on in our over-built world — and a gentle exhortation to lift our heads out of our screens and notice it all around us, even in the most unlikely places.

It’s an excellent, thought-provoking, sometimes melancholy but stirring book. After reading it, I went to hear Christopher speak on a panel at the Texas Book Festival. Christopher straddles diverse worlds through his profession as a lawyer and side gig as a writer of dystopian science fiction. So it seems fitting that in his spare time he explores the edgelands of post-industrial East Austin, seeking out heron rookeries along the river and keeping an eye out for ghostly coyotes and other wild creatures making their homes in slivers of abandoned urban landscapes.

Before reading his book, I’d heard a good deal about Christopher’s nature-embracing home, Edgeland House. Half buried in the earth like a Native American pit house, its triangular roofs shaggy with native grasses and forbs from the blackland prairie, the glass-walled house sits lightly on an old brownfield site in East Austin. Christopher and his family share the property, in his telling, with plentiful coral snakes and other creepy-crawly critters, plus owls, deer, foxes, naturalized monk parakeets, mesquites, rain lilies, and other wondrous flora and fauna. The divided structure of the house requires that its residents step outside — to be outdoors, at least for a few moments — to cross from its communal spaces to the private rooms. Being architecturally curious, I’d hoped that A Natural History would include more about the design and construction of the house and its rooftop prairie. I keep wondering about the experience of living in a structure that commits you to being half-outdoors in all weather. Is the house in any way a model for others, and can the concept be adopted for mass construction in eco-neighborhoods? Would anyone else want to live this way??

But that is perhaps a topic for another book. In this book, Christopher wants to open our eyes to the wilderness surviving in the neglected margins of our world, and especially within the post-industrial “wastelands” that keep humans out. The resiliency of nature gives him hope, although grief for what’s been lost is threaded through his observations too. “When I first started learning how to experience wild nature’s persistence in the margins of the city,” he writes, “I felt an almost childlike joy at the beauty of it…That sense of wonder never goes away, but over time it becomes tempered with realism. I’ve learned to see more clearly how outmatched the wild things are by our 10,000-year experiment in terraforming the Earth into a machine to feed us…”

But there’s a path to redemption, he says, and that starts with seeing, appreciating, and making room for wildness in our yards and in our cities. Nature will reclaim space if we let it — and sometimes even if we don’t. But by “breaking down the boundaries between ourselves and the world,” urges Christopher, we can make possible a healthier, ecologically balanced future.

Our children and children’s children deserve to live in and explore that world.

I welcome your comments. Please scroll to the end of this post to leave one. If you’re reading in an email, click here to visit Digging and find the comment box at the end of each post. And hey, did someone forward this email to you, and you want to subscribe? Click here to get Digging delivered directly to your inbox!

__________________________

Digging Deeper

Come learn about gardening and design at Garden Spark! I organize in-person talks by inspiring designers, landscape architects, authors, and gardeners a few times a year in Austin. These are limited-attendance events that sell out quickly, so join the Garden Spark email list to be notified in advance; simply click this link and ask to be added. Read all about the Season 8 lineup here!

All material © 2025 by Pam Penick for Digging. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited.

That’s an unusual and intriguing concept for a book!

It’s a unique book.

You vividly describe my childhood in SoCal as well, so this book naturally appeals to me too. My LA granddaughter and I attend the Forest School at Elysian Park, which though structured comes close to this kind of an “empty lot” experience — vanishingly hard to find! Thanks for the book tip!

I’m always glad to know about others who had that free-range childhood too. Aren’t we lucky?

I’ve been very curious about this book and appreciate your sharing more about it and the information and links about the authors fantastic home. I just added it to my library holds list and I’m hoping it’s enjoyable as an e-read. I find most garden books need to be on paper for me to really get into them, but I’m really trying to reign in the book buying.

You have more restraint than I, as my sagging bookshelves would attest. I think you’ll find this book just fine to read in a digital reader. I wouldn’t classify it as a garden book but rather an ecology-based memoir.

You are so good at finding the inspirational and the enticing! I have never heard of Edgeland House, and I am thrilled it is out there!

I hope to see it in person one day. It looks amazing in photos!

Loved reading about Edgeland. Such a cool idea for a house.

It’s such a bold design, isn’t it?